Get Lost, Be Found

What we think we want, what we get and what we need are sometimes the same things. Often they’re not.

When we’re lost, sometimes we’re just lost. And sometimes we find things we need that we didn’t know we were looking for.

Last summer, as I remembered the long and cold and seemingly unending prior winter, I floated the idea of going somewhere warm to ride bikes the following January to Spencer and Jonathan.

If you are a fan of the hero’s journey, you will recognize this as the call to adventure.

Starting up a company is many things. Predictable is not one of them. I had no idea what would need my attention six months down the line.

Then I thought whatever I would need to do in January could be done from Tucson. Might as well jump.

Now it was January.

I was in Arizona doing whatever I needed to do. I also brought the cold with me. I put my down jacket on in the morning. It was 28 degrees when I woke up, but it got up to 60 during the day.

Jonathan and I started off the trip at a bare bones hotel with a towering five-story atrium, bike-positive staff and pentagon-shaped benches in the lobby with 8-foot-tall backs that looked like they came off the set of the House Harkonnen palace in Dune.

The hotel’s key feature was its location, situated along the 60ish miles of riverside bike path that snakes around Tucson. We found a place to get breakfast burritos. The breakfast burritos each had at least a dozen eggs. It was like an omelet for a family of four in a tortilla.

The next morning our local tour guide Matt joined us for an out and back on the bike path.

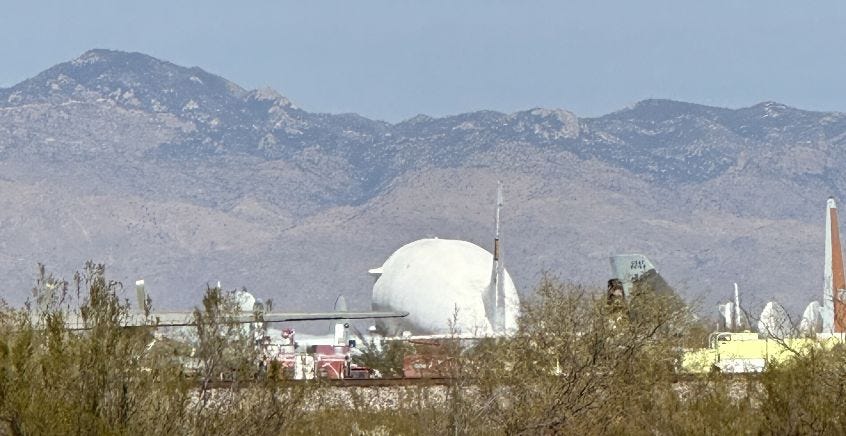

We went past an Air Force base that’s the home of the A-10 Warthog to an airplane graveyard near a baseball field where they park retired aircraft among them an Air Force 2 and a Super Guppy that I had previously only seen in the Hot Wheels version.

It felt great and shocking to be pedaling off Zwift, not on a trainer in my garage, with real physics, forward movement and around human beings.

Day two, Jonathan and I bundled up and headed out again for a quick 20 miles in the morning before moving to our housing for the rest of the week at Pace Ranch, a world-class spot that has hosted the world’s best professional cyclists and teams.

Pace Ranch is outfitted with everything you could possibly want on a cycling trip including a fully outfitted workshop, Normatec boots, all the floor space you and 10 of your friends might need to foam roll at the same time in front of a giant television while you watch bike races, an infrared sauna and a cold plunge that’s more like a small pool. I highly recommend staying there on your next Tucson excursion.

At the end of that ride, with half a mile to go, Jonathan pulled up and told me his seat post had slipped.

I looked over and saw that his seat was so low he was almost sitting on top of the frame. He looked like a kid on a BMX bike.

Jonathan is the kind of guy who would gut out anything and just keep going until the end. He insisted we just keep going.

You ride like that and you can tweak your knees that are used to being in a very specific position spinning the pedals at 80 to 100 rpm per hour.

If you tweak your knee at the beginning of a week where you’re going to ride three to five hours a day every day to build that World Tour-level fitness you need as a parent with a demanding job to carry you into the summer, you might find yourself on the injured reserve watching your friends go do that big gravel event you have on the calendar for July while you ice your knees and talk about the podium that might have been, the songs they would have sung about you for ages to come.

I insisted we stop.

We had nowhere to be.

The post was stuck in the frame and it took a thwack with the palm of my hand to get it unstuck and back up to height.

I became aware that I was outside and I was warm. It was at least 45 degrees.

Before I tightened the post, I examined it and saw there were residues of carbon paste in the frame and on the post, but not enough.

Carbon paste creates friction between the carbon in the post and the carbon in the frame that when coupled with the specified torque on the clamping mechanism keeps the post secure without any slippage. If you’re an engineer, you can explain this better than me.

The bottom line is, if you don’t use carbon paste, the carbon on carbon bond is too slippery and it won’t stay put.

You have to be careful when tightening a carbon seat post, because it can crack.

Using a torque wrench isn’t just a good idea, it’s mandatory if you want to avoid the possibility of destroying the post. We didn’t have any carbon paste and we didn’t have a torque wrench.

I had my multitool and used it to carefully torque the bolt to about as tight as I thought it should be and certainly tight enough to get us back to the hotel. Then we packed the truck and moved to Pace Ranch where we would stay for the rest of the trip. Jonathan and I both forgot about the slipped post.

The next day we headed out with Spencer and his friend Kip, both former pro cyclists with storied palmares they still celebrate in the front range to this day, for a 68-mile loop that our magic routing app turned into an 83-mile loop mid ride when we kept getting sent off course and lost over and over again.

The plan was to ride out to the edge of town to a mountain pass, using the bike path to stay out of traffic until we got to the big climb.

The app we used to route the ride had other ideas and we ended up riding on the edge of a road that in any other city I would call a highway. A river of cars flew past at 50 mph punish passing us over and over on the first six miles of the ride. The summer heat turns the asphalt in Tucson into six-foot strips of debris with curled up lips across the road between each road brick where the heat breaks the pavement and washes it with sand and gravel.

Jonathan’s post slipped. It needed carbon paste. We were at the very beginning of what would be a five-hour day and everyone was eager to ride.

Spencer knows Tucson well from doing training camps there over the years preparing to contest victories at some of America’s most storied pro races, like the Steamboat Stage Race where he once won the final stage criterium.

We happened to have stopped in the parking lot of an apartment complex with one of the largest American flags I’ve ever seen just a few blocks from a mini-mall with a bike shop.

We soft pedaled to the shop where we found a single mechanic and a bare bones setup. That’s usually a sign that it’s a serious shop with a skilled and helpful wrench. This turned out to be the case.

The mechanic stopped what he was doing, yanked the post out of the frame and slathered it with carbon paste.

Being on a ride with other people is like being in a car with your family on vacation. When it pulls over to stop, everyone uses the bathroom and gets snacks.

I looked over at the bikes in for repairs hanging neatly on hooks down one wall of the shop and saw a Trek Madone in the distinctive colors of the Trek-Lidl World Tour team. I thought, that’s Quinn Simmons’ bike, and said it out loud.

Without looking up the mechanic said, yeah, that’s his spare bike, he dropped it off yesterday.

The mechanic finished the job, we got back in traffic and did our best to navigate the route that kept sending us off course, at times onto actual highway highways, finally to the bike path and then onwards to Gates Pass where the view from the saddle out onto the valley was the actual apex of the ride.

Saguaro cacti stop growing at 4,000 feet, Matt and the internet told me so.

This ride kept going.

Going down real mountains with wind on broken roads brings life into focus, especially when it’s your third ride outside after three months on a trainer in a garage.

The faster I went, the shorter the intervals became between hitting the giant cracks running across the road. My chain jumped off the outside of my big ring. It took me a minute to slow down, get off the road and attend to it.

The chain looked like someone had tied it into a dozen knots, and even though it had derailed to the outside of the chainring, it had managed to loop around and get stuck sideways between the bottom bracket shell and the inside of the crank arm. This was a special moment.

A chain whammy like that can make your bike stop itself, not what you want to happen when you’re going 40 mph down a mountain with a guard rail and a big drop off to the side. I had the good fortune of stopping the bike electively and for that I was grateful.

I could see Spencer, Kip and Jonathan’s tail lights blinking off into the distance way down in the valley while I solved the rubik’s cube of the chain knots and carefully placed it back on the chainring. As I wiped the grease off my hands I thought maybe I would look into waxing my chain before the next bike trip.

I did a VO2 max interval for a few minutes to catch them, then they pulled off the side of the road to look at the route again.

I pulled out my phone to check the route as well and made a suggestion. Before I could put my phone away, they were back on their bikes. By the time I got my phone put away in my jersey, I had to chase for 10 more minutes to get back onto the group.

I got my intervals in for the day.

We kept getting lost and had to stop more times than I could count. The routing app sent us back and forth over the 10 freeway in rush hour traffic three times. On the final crossing, I did 700 watts up the freeway overpass climb before the light changed to get to the other side as fast as I could.

The sun was setting and the temperature was plunging when we reached the final straightaway back to Pace Ranch, an undulating climb up a sequence of rollers over the course of a few miles.

I was sitting third wheel. Kip and Spencer eased up. The dishes were done, we were all wiped. It was the perfect moment to give it some throttle.

I soft pedaled and dropped back a bit to let Kip and Spencer get a bit of a gap. This was a noncompetitive ride, but also not.

Then I let it rip, drilled it over the crest of the roller I thought was the last one before the turn off onto the dirt road to Pace Ranch. I was wrong, there was another hill on the other side of the hill we had just crested and I was out of gas.

Kip punched it past me and sprinted up the actual final roller, bulldozed over the top and became the winner of our not race. I sat up and spun the final 50 meters and when I got off the bike looked at the desert glowing red and edging towards darkness.

Back at the house, after we cleaned up, we sat in the living room watching the Tour Down Under wearing Normatecs and laughed about how much time we spent standing on the side of the road staring at an app that kept sending us the wrong way and riding with cars inches away from us feeling like we were probably going to die today.

We’ll die one day, but it wasn’t this day.

We made it to the end.

The post didn’t slip.

-Andrew

*this newsletter was written by Andrew Vontz, a human being on planet earth, without the aid of AI

New episodes of the Choose the Hard Way podcast are coming soon, I’d appreciate it if you could share this newsletter with your friends and follow @hardwaypod on Instagram.

That’s where I frequently post stories about adventures, bikes and wrong turns taken while doing hard things with friends in austere environments like my backyard, the chicken coop and freeways in Tucson.

LISTEN: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | YouTube | Stitcher

Choose the Hard Way is the podcast about how doing hard things builds stronger humans who have more fun with host @vontz.

Copyright (C) 2025 Big Truck, LLC. All rights reserved.

Our mailing address is:

925 Barnestown Road, Hope, ME 04847

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe